I’ve always loved books. Everything from the cover art, the fonts, to the way they smell. As physical works of art, they’ve always astonished me. As an escape from a routinely violent household, they were indispensable. They were also an enormous source of frustration, sadness, and shame. While I would be categorized as an early reader (Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree, aged 4) and talker, what I was, was a really good mimic, listener, and a master of maladaptive coping skills, skills that (sometimes) saved me from being beat by my mother. We had stacks and stacks of books in our home, but the only children’s book was a set of Winnie the Pooh. I gravitated towards those books, and had one of in my hands most days. I devoured the pictures, trying to make connections between the still images. One of my aunties, Rose, would read one of those books to me whenever she came over. The Honey Tree was the book that she went back to, over and over. I memorized the book, the way she read it, her inflections, so when I sat and “read” the book aloud, I sounded as if I were some kind of little genius. Thing is, despite all the preschool, words and letters were a source of pain. In fourth grade, I’d be diagnosed with dyslexia—I wouldn’t get any real help with it until a few years after that—but until then, we had no idea what was happening with me, aside from my mom thinking, and saying, I was stupid.

Before I get too far into the weeds, I want to tell you what dyslexia is not. It isn’t just words and their meanings being elusive and almost impossible to apprehend. It isn’t letters swimming in your vision like a bowl of Alpha-Bits. There is no common experience. It isn’t the same for everyone.

I’ve met a very small handful of people who experience it like I do. Dyslexia is a constellation of effects that impede you on multiple levels. One way to think about it is this: You know exactly what you’re making for dinner. You have all the ingredients, the pots and the pans, you’re ready to cook. As soon as everything is assembled in front of you, you have no idea what all this stuff in front of you is. Was I meant to throw it out? Put it away? There’s a lot of stuff here, so it must have had a purpose. But I guess the purpose of it is beyond me. Or, you’re stumbling through reading aloud in middle school and you routinely confuse organism with orgasm and everyone laughs at you and you’re sent to the principal’s office for disrupting the class, and being that every time you read aloud you make several embarrassing mistakes, you are routinely sent to the principal’s office because your teacher thinks you’re willfully disruptive. You get sentenced to in-school suspension for the rest of the year and no one believes you when you tell them those were honest mistakes. Or, you constantly misspell “simple” words and a few weeks later, you’re put on a little yellow school bus and are put into classes with kids who are barely verbal. Or, after you’ve read something to yourself, or aloud, you feel as if you just went a few rounds with Mike Tyson.

It’s not just that dyslexia separated me from written and (sometimes) spoken language, it also separated me from the world because my verbal and written mistakes turned into shame weights, weighing me down, making me too heavy to participate in most things. My desire to participate in anything waned because my facility with the spoken and written word wasn’t up-to-par with that of my peers. So, I retreated inward. I crafted an inner-world where everything I said and wrote conveyed my precise message. In this inner-world my oratory skills were unparalleled, and I’d written books and essays that brought value to people’s lives. My retreat into that world was rocket fuel for my imagination. The number of aliens I met, dragons slayed, supervillains vanquished was legendary. But all that had no bearing in the mundane world because I wasn’t able to accurately articulate the wonders I had imagined. Few things more frustrating (humiliating, really) than having something so majestic in your head, and not being able to share it in a way that others can easily understand.

But there were people out there who understood. They may not have had a disability, but they understood how imaginary worlds mattered. The difference between me and them was that they had the ability to present those worlds, to others, in a coherent and fascinating way.

My mother took off with one of her numerous boyfriends and left me with Rose. We joked and laughed, cooked together, and it was one of the few times I felt safe as a kid. We even went to Woolworth’s together.

F.W. Woolworth’s was Wal-Mart, 7-11, Marshall’s, Target, and K-Mart all in one store. There was really no rhyme or reason to why, as a kid, it was the grail of places I wanted to visit. When I finally got to go, I wasn’t disappointed. Despite it being a little overwhelming, it was everything I wanted. All I really knew was the housing projects I lived in, so going to Woolworth’s was like stepping through the wardrobe and into Narnia.

We looked, touched, tried some things on—treated the place like a museum where you were allowed to interact with the exhibits. As we were leaving, my auntie got us each a soda and a hot dog. Two RC Colas with one hotdog with ketchup (hers) and one with all the mustard ever made in the world (mine). I was never allowed to have fun food, so being in Woolworth’s, eating like that, made that day the best day of my life. But it was about to get a whole lot better.

Comic book spinner rack with imaged of Richie Rich, Spider-Man, Archie, and Superman

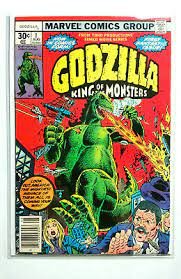

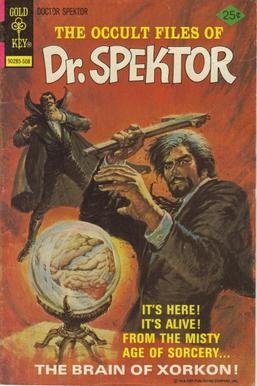

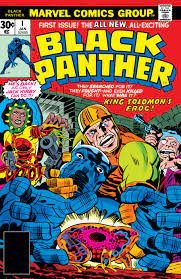

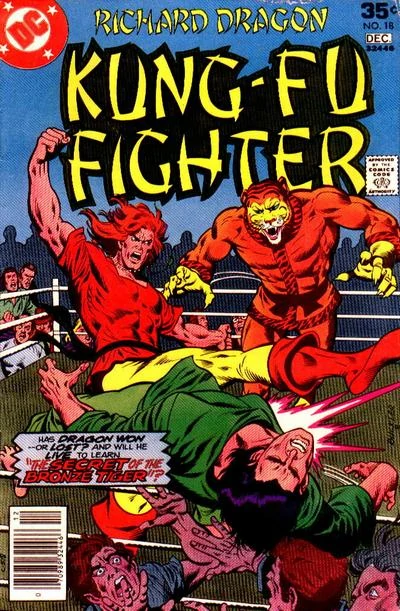

A few feet away from the counter where we were eating was a spinner rack stuffed with comic books. No separation between publishers. The Richie Rich comics were next to Godzilla that was next to Action Comics. My heart beat faster as me and my mustard drenched hands moved towards the rack, as if compelled. I heard my auntie sigh and in a very stern voice she said, “You can get four. Just point because I don’t want your nasty hands ruining them.” I chose my four (photos included) and something happened. It’s really difficult to explain. Do you remember when you found your thing—or your thing found you? A thing that was going to be with you for the rest of your life, the thing that brought you a level of happiness you didn’t know existed, up until that point? That’s what I felt like as I clutched that bag full of comics in my (now washed) hands.

As soon as we returned to Rose’s apartment, I hopped on the couch and poured through them. They were so different than the children’s books I had access to. Granted they both contained still images with words, but the comics had several pictures on the page and a whole lot of damn words. I saw how each image fed into the next—not always in the best of ways, but there was a design to it.

To be frank, I didn’t know what I was doing when I started doing it. I’d go through each comic several times. I wouldn’t even attempt to tackle the words, I just engaged with the images. Used the dream machinery of my inner-world to fill in the gaps between the panels. What happened that allowed for this to happen? Once I had what I thought was a complete story in my head, I attempted the Herculean task of trying to read the words. I sounded out each and every word. Rose corrected me and explained to me what some of the words meant. Once I had a clearer (as clear as dyslexia would allow it to be) understanding of the words, how they were arranged to propel the story forward, and matched them with the story I’d crafted, I was amazed at how close my story was to what was being told on the page. The more comics I read, the (relatively) easier my relationship with words became. Hell, comics (and the help I received later) gave me enough confidence that my dyslexic behind was able to teach my grandfather how to read. I was able to fill in the blanks between still images, read the images in the panels to get an idea of the narrative tension and direction of the story, craft my own narrative, and then struggle through the words to reveal what was actually happening in each issue of each comic that I read.

In no way am I saying that learning to read comics was any kind of silver bullet when it came to reducing the impact of my dyslexia. Not at all. What I am saying is that comic books stopped me from hating reading and writing. Point of fact, just the opposite. Those four-color wonders gave me an appreciation for what letters, words, sentences, and paragraphs could do. I even fell in love with words that weren’t real words: THWACK! A word could be a sound? Amazing.

Even at my advanced dinosaur age, I still use those same techniques to hack my dyslexia. Make no mistake, dyslexia is always there, ready to trip you up, if you let your guard down, even for a minute. But I’ve found some effective tools to get around it, to not have it be the debilitating problem it used to be. I teach these techniques to others and sometimes it works for them, and sometimes my techniques fall far short. And despite what these techniques have done for me and others, dyslexia still sucks, though. If it were a person, it would have to catch these hands.

What’s a little bit nuts is that I’m known for being a voracious reader, fairly decent writer, and an eloquent speaker. Hell, I’ll own all of it—especially the speaker part because I also had a stutter as a kid and now, I’m not too shabby on the mic. What people think is an ease and confidence with words is me giving years of sadness, shame, frustration, bullying, and grief a middle finger composed of the twenty-six letters of the English alphabet.

My way isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution to muddling through dyslexia. It is a solution. Not the way, but a way to try to limit its hold so you can move through and the world, and tell others about your experiences in the way you deserve to.