“When we critique Hip Hop, we have to be prepared for the backlash. We have to be prepared for the possibility that our relationship to and with it might change—maybe not for the better. It is profoundly foolish to expect our culture to be free from the bullshit that exists in the world. If we do, then we don’t have a culture.”

Read MoreBig Man Understandin'

I have Summas and Magnas all over the place, but the abilities of my mind have routinely taken a backseat to what others think my body can do, or what my body should be doing, for them.

Read MoreIn Defense of Hot Topic

If your child invites you into their world, you graciously and humbly accept the invitation and you do whatever is necessary to enter. You enter, you shut up, and you let them lead. You let them show you what they deem important. You give them your undivided attention. As a parent, you should never be the reason your kid lacks the ability to be open and vulnerable.

Read MoreFont used to simulate dyslexia

Dyslexia And The Four-Colored World aka THWACK! Those Letters

I’ve always loved books. Everything from the cover art, the fonts, to the way they smell. As physical works of art, they’ve always astonished me. As an escape from a routinely violent household, they were indispensable. They were also an enormous source of frustration, sadness, and shame. While I would be categorized as an early reader (Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree, aged 4) and talker, what I was, was a really good mimic, listener, and a master of maladaptive coping skills, skills that (sometimes) saved me from being beat by my mother. We had stacks and stacks of books in our home, but the only children’s book was a set of Winnie the Pooh. I gravitated towards those books, and had one of in my hands most days. I devoured the pictures, trying to make connections between the still images. One of my aunties, Rose, would read one of those books to me whenever she came over. The Honey Tree was the book that she went back to, over and over. I memorized the book, the way she read it, her inflections, so when I sat and “read” the book aloud, I sounded as if I were some kind of little genius. Thing is, despite all the preschool, words and letters were a source of pain. In fourth grade, I’d be diagnosed with dyslexia—I wouldn’t get any real help with it until a few years after that—but until then, we had no idea what was happening with me, aside from my mom thinking, and saying, I was stupid.

Before I get too far into the weeds, I want to tell you what dyslexia is not. It isn’t just words and their meanings being elusive and almost impossible to apprehend. It isn’t letters swimming in your vision like a bowl of Alpha-Bits. There is no common experience. It isn’t the same for everyone.

I’ve met a very small handful of people who experience it like I do. Dyslexia is a constellation of effects that impede you on multiple levels. One way to think about it is this: You know exactly what you’re making for dinner. You have all the ingredients, the pots and the pans, you’re ready to cook. As soon as everything is assembled in front of you, you have no idea what all this stuff in front of you is. Was I meant to throw it out? Put it away? There’s a lot of stuff here, so it must have had a purpose. But I guess the purpose of it is beyond me. Or, you’re stumbling through reading aloud in middle school and you routinely confuse organism with orgasm and everyone laughs at you and you’re sent to the principal’s office for disrupting the class, and being that every time you read aloud you make several embarrassing mistakes, you are routinely sent to the principal’s office because your teacher thinks you’re willfully disruptive. You get sentenced to in-school suspension for the rest of the year and no one believes you when you tell them those were honest mistakes. Or, you constantly misspell “simple” words and a few weeks later, you’re put on a little yellow school bus and are put into classes with kids who are barely verbal. Or, after you’ve read something to yourself, or aloud, you feel as if you just went a few rounds with Mike Tyson.

It’s not just that dyslexia separated me from written and (sometimes) spoken language, it also separated me from the world because my verbal and written mistakes turned into shame weights, weighing me down, making me too heavy to participate in most things. My desire to participate in anything waned because my facility with the spoken and written word wasn’t up-to-par with that of my peers. So, I retreated inward. I crafted an inner-world where everything I said and wrote conveyed my precise message. In this inner-world my oratory skills were unparalleled, and I’d written books and essays that brought value to people’s lives. My retreat into that world was rocket fuel for my imagination. The number of aliens I met, dragons slayed, supervillains vanquished was legendary. But all that had no bearing in the mundane world because I wasn’t able to accurately articulate the wonders I had imagined. Few things more frustrating (humiliating, really) than having something so majestic in your head, and not being able to share it in a way that others can easily understand.

But there were people out there who understood. They may not have had a disability, but they understood how imaginary worlds mattered. The difference between me and them was that they had the ability to present those worlds, to others, in a coherent and fascinating way.

My mother took off with one of her numerous boyfriends and left me with Rose. We joked and laughed, cooked together, and it was one of the few times I felt safe as a kid. We even went to Woolworth’s together.

F.W. Woolworth’s was Wal-Mart, 7-11, Marshall’s, Target, and K-Mart all in one store. There was really no rhyme or reason to why, as a kid, it was the grail of places I wanted to visit. When I finally got to go, I wasn’t disappointed. Despite it being a little overwhelming, it was everything I wanted. All I really knew was the housing projects I lived in, so going to Woolworth’s was like stepping through the wardrobe and into Narnia.

We looked, touched, tried some things on—treated the place like a museum where you were allowed to interact with the exhibits. As we were leaving, my auntie got us each a soda and a hot dog. Two RC Colas with one hotdog with ketchup (hers) and one with all the mustard ever made in the world (mine). I was never allowed to have fun food, so being in Woolworth’s, eating like that, made that day the best day of my life. But it was about to get a whole lot better.

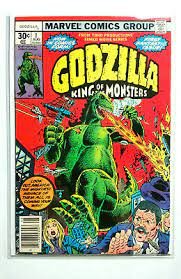

Comic book spinner rack with imaged of Richie Rich, Spider-Man, Archie, and Superman

A few feet away from the counter where we were eating was a spinner rack stuffed with comic books. No separation between publishers. The Richie Rich comics were next to Godzilla that was next to Action Comics. My heart beat faster as me and my mustard drenched hands moved towards the rack, as if compelled. I heard my auntie sigh and in a very stern voice she said, “You can get four. Just point because I don’t want your nasty hands ruining them.” I chose my four (photos included) and something happened. It’s really difficult to explain. Do you remember when you found your thing—or your thing found you? A thing that was going to be with you for the rest of your life, the thing that brought you a level of happiness you didn’t know existed, up until that point? That’s what I felt like as I clutched that bag full of comics in my (now washed) hands.

As soon as we returned to Rose’s apartment, I hopped on the couch and poured through them. They were so different than the children’s books I had access to. Granted they both contained still images with words, but the comics had several pictures on the page and a whole lot of damn words. I saw how each image fed into the next—not always in the best of ways, but there was a design to it.

To be frank, I didn’t know what I was doing when I started doing it. I’d go through each comic several times. I wouldn’t even attempt to tackle the words, I just engaged with the images. Used the dream machinery of my inner-world to fill in the gaps between the panels. What happened that allowed for this to happen? Once I had what I thought was a complete story in my head, I attempted the Herculean task of trying to read the words. I sounded out each and every word. Rose corrected me and explained to me what some of the words meant. Once I had a clearer (as clear as dyslexia would allow it to be) understanding of the words, how they were arranged to propel the story forward, and matched them with the story I’d crafted, I was amazed at how close my story was to what was being told on the page. The more comics I read, the (relatively) easier my relationship with words became. Hell, comics (and the help I received later) gave me enough confidence that my dyslexic behind was able to teach my grandfather how to read. I was able to fill in the blanks between still images, read the images in the panels to get an idea of the narrative tension and direction of the story, craft my own narrative, and then struggle through the words to reveal what was actually happening in each issue of each comic that I read.

In no way am I saying that learning to read comics was any kind of silver bullet when it came to reducing the impact of my dyslexia. Not at all. What I am saying is that comic books stopped me from hating reading and writing. Point of fact, just the opposite. Those four-color wonders gave me an appreciation for what letters, words, sentences, and paragraphs could do. I even fell in love with words that weren’t real words: THWACK! A word could be a sound? Amazing.

Even at my advanced dinosaur age, I still use those same techniques to hack my dyslexia. Make no mistake, dyslexia is always there, ready to trip you up, if you let your guard down, even for a minute. But I’ve found some effective tools to get around it, to not have it be the debilitating problem it used to be. I teach these techniques to others and sometimes it works for them, and sometimes my techniques fall far short. And despite what these techniques have done for me and others, dyslexia still sucks, though. If it were a person, it would have to catch these hands.

What’s a little bit nuts is that I’m known for being a voracious reader, fairly decent writer, and an eloquent speaker. Hell, I’ll own all of it—especially the speaker part because I also had a stutter as a kid and now, I’m not too shabby on the mic. What people think is an ease and confidence with words is me giving years of sadness, shame, frustration, bullying, and grief a middle finger composed of the twenty-six letters of the English alphabet.

My way isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution to muddling through dyslexia. It is a solution. Not the way, but a way to try to limit its hold so you can move through and the world, and tell others about your experiences in the way you deserve to.

Money Is A Language You Have To Know How to Speak

I never understood how Wu Tang Clan’s C.R.E.A.M. (1993) became the ‘let’s get this’ anthem. If you listen to the song—a tune for the ages—it’s mad depressing. It seems to have had a resurgence with the rise of LLC Twitter and all of their poor and sometimes dangerous advice. I’m like, damn! Have you actually listened to the entirety of the song and not just the chorus? This song was never anthemic to me, It always felt, and feels, like a very profound warning about the pursuit of money—the whole 50 Cent ‘Get Rich or Die Trying’ mentality. As a kid from a family of no means, who grew into a young adult with no means, fumbling through undergrad on a unicycle of scams to make enough money to eat and buy books, this song was (I admit) seductive. But my reality was: ‘Debt rules Everything Around Me (D.R.E.A.M.) I have no money/all these damn bills/y’all.’

When you come from a place of poverty, your relationship with and to money is all skewed. While I won’t make any generalizations—aside from our skewed relationship with and to money—Most of us suffering from poverty consciousness either over or undervalue money. We place too much importance on it, in either direction. On one end of the poverty consciousness spectrum we’re on that 50 Cent shit. On the other, we overthink or outright reject any financial windfall because we feel we’re unworthy. It took me a long time to reset my relationship with and to money. But I won’t front. I sometimes revert back to my scarcity mindset and make poor financial decisions.

I’m not going to get too much into those decisions, but let’s just say I don’t have the amount of sneakers I do because I’m opening a store. Retail therapy is my maladaptive coping skill for when I’m feeling uneasy about money. Right before the pandemic shut down most of my ventures, I received a large check from a client. I paid off two credit cards, which was dope. Saw my credit score shoot up a few months later. But the money I earmarked for savings and the Roth? My family got presents everyday for a month. I bought more sneakers than I knew what to do with, and we went out to eat every single night for a few weeks. When I emerged from my spending fog, almost all of that huge check had evaporated. And I felt guilty. It was that same icky, you’re not worthy guilt feeling like when I overeat on things I have absolutely no business eating. But unlike most folks who are from the same social context as me, I’ve been lucky to have several mentors, financial geniuses, who took me under their wings to give me all the jewelry.

In no way am I advocating capitalism or a money above all else ethos. But we live in a time and context where we need money to survive, live, and thrive. And just like a weapon, I’d rather have it and not need it instead of needing it and not having it.

Money/It’s a Gas

Immediately before writing this, I was calculating the costs for our daughter’s college education. Based on what she wants to major in and the school she wants to attend, we’re looking at a pretty steep six figures. While my wife and I have some cash in her 529, but after doing the following equation: Time Until College x Monthly 529 Contributions = We’re Going To Have To Quadruple Our Monthly Contributions. And we live in California, so we’re already out $50 as soon as we wake up. This keeps me up at night. Financial planning for our daughter’s future—a future that seems to be in more and more jeopardy because of a subset of people who seem determined to ruin society—makes me question the necessity of saving for something that is, at this moment, a want, not an immediate need. Once again, I’d rather have it and not need it, but still. Money impacts every facet of our lives—I wish this weren’t so, but that’s the moment we’re in and I want to be able to thrive in it.

I’ve been poor. Really poor. I don’t ever want to feel that kind of stress again. I for damn sure don’t want my daughter to even know that kind of stress exists. As a parent, one of my jobs is to make sure that my daughter is better off than I was. She’s already so much cooler and more comfortable in her skin, than I was or am. But I want to make sure that her mom and I set her up to the point that money is not her primary concern. Once the money monkey is off her back, she’ll be freed up to build the life she needs and wants.

My reconciliation with money started with a conversation with a former friend, Corey’s, dad. Bill Gillquist (R.I.P.) was an executive with the Honeywell corporation. He came from humble beginnings, became disabled because of polio, and went on to advance in his chosen field. They had a gorgeous home in South Minneapolis, a Porsche and Mercedes in the garage, and Corey had every single PC computer system that dropped—Corey is a genius computer forensic investigator to this day. This measly paragraph illustrates how a parent having money (and generously sharing with their children) will set kids up to the point where they can pursue their dreams, without deferring them because they cannot afford to do anything, except survive.

I came over before Corey arrived and like always, his parents (Corey and Sylvia) invited me. Two of the most generous people you could meet. We used to eat them out of house and home, but they were always cordial and welcoming. Bill and I were sitting in their TV room when Bill, somewhat aggressively asked: “What the fuck do you think you’re going to do with your life? I know you’re in college, but what are your plans after that?”

Talk about feeling attacked. My dyslexic ad stuttering ass was trying to calm down before I answered, so I wouldn’t sound horrible out of place. I shrugged and tossed out something about wanting to be a filmmaker. “Well, you’re not going to the best college for that.”

Ouch.

“What do your parents do?” This broke me. My mom only ever had odd jobs and didn’t have any real investment in my future and I didn’t know my father, other than meeting him seven random times. I then unburdened myself. Not sure how long all that was buried, but it came spilling out. I explained how the entire financial burden of university was on me, how I grew up poor and abused—how I had no idea what the hell I was doing and was utterly terrified and that I came over to their house to see Bill and Sylvia as much as I did Corey, because I wanted to see what functional and loving parenting looked like.

Bill was quiet, quiet for a long while. The embarrassment resulting from what I’d just shared began to sink in. I got up to leave.

“Sit down, “ Bill commanded. “You have to change how you’re thinking about everything. I can’t do anything about your relationship with your parents. That’s fucked up. But I can give you something to think about in regards to money. How to make it and how to keep it.”

Why wouldn’t I listen to a rich guy? I was all ears.

"You want to get rich? Hang out with people who earned every penny of their money. Hang out with people who made their wealth. Avoid people who inherited their money. I mean, by all means hang out with Corey, but he’ll inherit a lot. Honestly, he’ll inherit a lot but will also make his own with that computer shit. He’s a genius. So that’s a bad example. Most people who inherit their money don't know how it works. It’s always been there, they’ve always had it. There’s no process for them, just financial consistency—money earned and managed by someone else. It’s a fact, not an aspiration.”

He dropped another one on me, something I've heard before.

“Money is a language you have to learn how to speak. If not, you'll never be able to attract it. What I mean is you have to understand the where, how, and when to go after it because it won’t come to you." And then, “Anyone who says, ‘money isn’t the answer’ is too broke to even ask the question.”

As cryptic as these were, they made complete and total sense to me. Not the words themselves, but the sentiment behind them: Stop being afraid of money, stop misunderstanding its utility, stop keeping my distance from it, and go and get me some.

The conversation also forced me to reflect on how I routinely engaged in financial self-sabotage, mainly from not knowing (or advocating) for my worth. I don’t think I’m in the minority when I say that knowing how much I should charge for a service, or how to negotiate a raise is one of the most difficult things I ever have to do.l What is my labor worth? This is precisely why having open and honest conversations with your vocational peers is so important. To treat money as taboo is gives us no power in negotiating what we should be paid. Once there is radical financial transparency, most of us will become less afraid and getting our coins.

Another heavy de-scaling of the eyes was when I switched from: advocating for what I was worth to getting paid what I deserved. Divorcing my worth from my earning power was freeing. I’m priceless, dammit. But you need to pay me this, for me to do that for you. It wasn’t an easy shift because so many things in our society link are self-worth to our ability to earn. For me, once I was able to make my earning potential and my self-worth separate things, I became more confidant. I was able to focus on my experience and my skill-set—I know what I can do, and what I can do is dope—and not have my self esteem rise and fall according to home much income I was making at a given time. Not to say that I don’t slip here and there, taking on an excess amount of stress in pursuit of money, but it happens less and less now than it did in my early 20s.

So I was in a much better place to receive some more money wisdom, almost 29 years to the day, after I spoke with Bill Gillquist.

I had just entered my favorite coffee shop in Berkeley and sitting in the back patio area was one of my favorite writers and thinkers. Of. All. Time. I’m not going to name drop because I don’t want to blow up his spot. Me? I’m the cold call champion of the world so I approached him, turning up my charm and extra twenty percent, and introduced myself. I told him that I taught two of his books to my undergrad students and that his interview on a recent podcast changed the trajectory of a book I was writing. I joked he was my mentor, despite my never meeting him prior to that day. He laughed really loudly. He was exceedingly nice and asked if I’d join them.

Damn the COVID. I collected my coffee and sat my happy ass down.

He introduced me to his coffee companion and he was also nice and eager to have a conversation. We talked about tech ethics, digital humanities, folklore, popular culture, why email is more intrusive than phone calls—one of the best moments in my life. And I have had my fair share of adventures.

The we started to talk about money. Not money per se, but how it moves though and affects our lives and society.

If my unofficial mentor was a certified millionaire, his companion was a certified billionaire. With a B. And with all my research, I don’t think he was on some "Le secret des grandes fortunes sans cause apparente est un crime oublié, parce qu’il a été proprement fait” Balzac shit.

He gave me all the free jewelry, but I’ll give you the points that impacted me the most:

“The gulf between fame and wealth is enormous. There are a lot of famous broke people. The general public has no idea who I am but my kids and their kids and their will never want for anything. People seem t be chasing the wrong things.”

“Getting rich is easy. If that’s your goal. The right investments, save more than you spend. But what’s rich? Rich ends. Wealth doesn’t. Wealth becomes a culture.”

“Money doesn’t buy happiness, but wealth ensures security. Knowing that I’ll never be hungry, that I’ll always have shelter takes two of the biggest stressors off my plate and I can focus on other things. Being in constant survival mode will take years off your life.”

“We can rail against money and how it’s evil all we want. Getting it can cause harm, but I’ve done more good with my wealth than I ever did screaming eat the rich with other people screaming the same thing.”

I was floored. Stunned into silence. It would’ve be easy to write of the proclamations of an incredibly wealthy white man, especially in the Bay, but his words hit me at the right time, that time being simultaneously taking care of elders, other family members, all while while saving for retirement and my child’s college fund. Not to mention just the general level of expensiveness living in the Bay Area.

Brutal truth: More money would make my life, and the lives of my family, better. No need for calligraphy around this. More money, fewer problems.

This exchange was in conversation with what Bill Gillquist dropped on me decades prior. Comparing and contrasting the two allowed me to recognize and understand the following:

Money is a real and tangible thing. It can and does provide security and stability. It moves you from survive to thrive.

Money is a concept. It is a symbol, albeit one with positive and negative material impact.

Money isn’t inherently evil.

The worth of your personhood is not connected to how much money you have.

Along this same note, I have to stop thinking about my age as some kind of ‘earning window.’ I’m writing this on my 49th birthday and I find myself speaking in those terms: “I have, maybe 6 years left before I start to look my age. I need t make all the money I can before I start to look old and no one will hire me.”

Entrepreneurship is looking more and more desirable.

The more money I have, the more people I can help.

It is tempting to lose oneself in the pursuit of it. As the rich folks say, ‘The game of it.’ It’s crazy to talk to people who think money is a game when you’re a missed check away from losing everything.

I need a lot more money.

My conundrum is how to get more money without abandoning my family and my values? I’ve worked in high-earning positions before and while the money was wonderful (ohmigod is was wonderful) but I wasn’t a very good person. I was short with my wife, absent from our relationship—I couldn’t turn off high-power-guy and he invaded our home. Let’s just say separation was on the table. I’m not that same guy, anymore. I’m a better husband. I’m a father, now. I’ve seen the world I want to live in, that I want my daughter to inherit, and it’s not extractive or exploitative.

So I’m left with the aforementioned conundrum: How do I make enough money so me and my people are well-taken care of, without losing the person who’ve I become? A person who I actually like?

Why Can't Auntie Be the Chosen One

When I was younger, I never cared too much about being young. Well into my middle-age, I still don’t care too much. The majority of my friends are older and the only younger people I spend any time with are my daughter, her friends and cousins, and my students. I’m not “anti-young” or “anti-young people” but unlike so many of my generation and almost all of media, I don’t chase youth. I don’t fawn over it. I don’t lament its passing. Do I miss what my younger body could do? Hell, yes. I miss jumping off things and not worrying whether or not my knee will collapse (again) and I’ll have to have knee surgery (again). There are more creaks, and I’m stiffer than I’ve been, but I just take frequent deep breaths and yoga through it all to get back to some semblance of fluidity.

The truth of it is that I didn’t think I’d live this long. As I write this, I’m a few months past my forty-ninth birthday. That I made it through the poverty and bullets and knives and law enforcement…and being Black? It’s nothing short of a miracle that I’m sitting at Souvenir Coffee on Solano avenue in Albany, Californian writing this. A far, far cry from the rat and roach infested projects I grew up in. Maybe it’s this, my formative circumstances, that have insulated me from trying to ride the youth dragon.

When and where I grew up, young people were either currency or collateral damage. And as soon as I was ‘grown enough’ in size and body, I bolted from my origins and into an uncertain future. Didn’t matter what the future was, as long as I could leave the horror behind. I mean, of course, there were some dire times in my adult life, but being older, I had the agency to do something about it. I was no longer at the mercy of parental inattention and abandonment, or neighborhood warfare. There’s something mighty powerful about having the ability to protect and advocate for yourself on multiple fronts. I’d dare say it’s a heady feeling.

I recognize that I’m amongst a small contingent of outliers. We’re a rare breed, those of us embracing the grey hairs—even on our nether regions—the lines in our faces (hopefully, mostly from laughter) and relishing our march to the final destination. If I’m honest, I’ve never felt more energetic, creative, focused, determined and, shit, sexier than I do right now. I’ve gotten more accomplished in my 40’s than all my years prior. And very little of it was accomplished because I felt my youth was running out. Just the opposite. I’ve been able to do so much because I’ve made my peace with time and age and I can no longer be bothered by things I can’t control. I’m going to get older. I’m going to get slower. I’m going to have fewer opportunities. Instead of fretting, I’m picking my shots. No more throwing haymakers that’ll eventually tire me out. My shit is precise. I’m only throwing what’s necessary, and what I’m pretty sure will make an impact.

And we need more stories like this. Not individual anecdotes, but full on stories about adults leveling up, generated by the various machines of popular culture.

We’ve had more than our fair share of coming of age stories focused on young people struggling up from childhood into an adulthood. It’s time for us to remix the genre of the Bildungsroman to include moral, psychic, spiritual, and emotional growth of and for the over forty set.

It’s not like, once you hit this imaginary thing called adulthood, you stop growing. All adventure doesn’t stop once you’ve lost your virginity or matriculated from high school to college or college to vocational school. I’d argue, once childhood things are firmly behind you, the adventure really kicks in.

We’ve had the wanderlust, restless and culturally clueless Eat, Pray, Loves and the 50 Shades of sexual experimentation, but so many of these portrayals are from a profoundly monocultural lens, not to even comment on class.

This is why Radha Black’s 2020 gem of a film, The Forty-Year-Old-Version was such an important film to me. Not only was it written by and starring and directed by a Black woman, it showed with an almost uncomfortable honesty the sacrifices and compromises so many of us (especially Black and other women of color) make for any kind of hint of stability. It also shows how self-destructive we can be in denying our dreams. If you haven’t seen it, please seek it out and give it a look.

While I love this movie and what it did for me, I want to see this same honesty and attention presented in fiction. I don’t care if it’s on tv, books, or in the cinema.

I want to see a 48-year-old man not collapse under the grief of his partner’s death, but instead use his grief as a generator to become a more refined, efficient, and more than worthy of new love version of himself.

I want to see a couple in their late middle age, no previous marriages or children, in a screwball romantic comedy. With semi-gratuitous sex scenes that are passionate but not nearly as athletic as they were twenty years prior. Show we the wrinkles and the folds.

I wasn’t to see a fifty-something dad who isn’t an immature fuck-up, but a loving and caring father whose children no longer need him, but want him to be in their lives because he is a good man and will always have their backs.

But most of all, I want to see an auntie in her forties or fifties receive a letter from a school of magic delivered by a regular ass pigeon. When she opens the letter, it’s an invitation to finish her degree (when her sister passed, she took in her niece and nephew and raised them as her own, putting her studies on hold). I want her to accept the invite, attend the school and discover that she’s destined to combat an ancient evil, for she is the chosen one. While dealing with her new status as the chosen one, she’s also navigating being considerably older than her peers—around the same age as a handful of her instructors. At the conclusion of the series, I want her to whoop the baddie’s ass and then live the rest of her life the way she wants to.

If I can’t have this, can I have a group of women who decide to become a superheroes in their 50s? They always had the power, they’re now deciding to use it. Not as some kind of mystic oracles that give advice to younger heroes, but they’re the ones out there, kicking all the ass.

That we stop paying public attention to women when they reach a certain age—add race to this and we’re invited to stop paying attention to them earlier than we do with their white counterparts—is ridiculous. Do people not understand that a journey of self-discovery or self-realization can happen at any age? We’ve had more than enough stories about GenX and Boomer manchildren being forced to mature and become more responsible. These caricatures times have come, but not yet gone. They’re long past their expiry date.

Let’s have a blooming of early through late middle-aged women having adventures, casting spells, visiting uncharted territories, slaying dragons—winning the hand of their chosen man, woman, non-binary person. Hell, all three. If auntie is poly, let her poly. It’s time to stop painting older women as the villain or the meddlesome mother-in-law or jealous never-been-married conniving “cougar.”

Let auntie be the chosen one. We’d all be better for it.

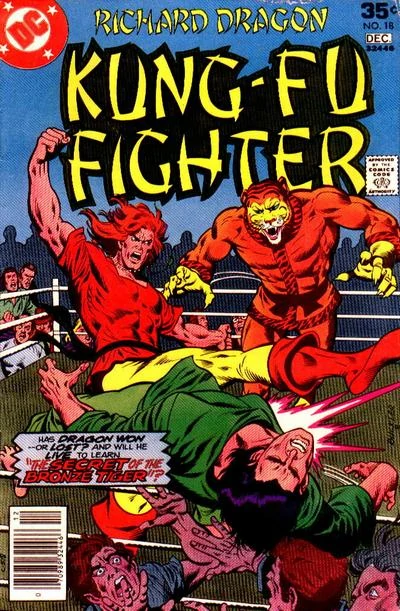

Rows of multi-colored ‘zines.

The Inevitable Impulse to Change the World

For those who don’t know, Kinko’s wasn’t only a ubiquitous copy center from 1970 - 2008, it was also the launchpad for so many young GenXers creative hopes and dreams. When you walked into a Kinko’s (now, FedEx Office), there was no doubt in your mind that this was a place to get work done. With an aesthetic reminiscent of a dystopian shopping center, this no-frills operation, with their computers lined in stately rows, their multifunction copiers—which looked like science fiction to a generation reared on mimeographs—and their helpful, yet vacant staff, it is no wonder that the creativity that was assembled within those walls got out into the world.

But maybe I’m a little ahead of where we need to be. Let’s deviate a bit. I promise it will all tie together.

I continue to find it fascinating that Generation X has been labeled as slackers, the disaffected; the invisible generation sandwiched between the more consequential Boomers and Millennials. I’m of the mind that Black and POC GenXers had a vastly different generational experience than white GenXers. There has been very little media that has captured the spirit, the sheer vibrancy of Black and POC GenXers. Of late, there has been an article hereand there, with the New York Times being particularly uneven in their coverage, but overall—shouts out to Chuck Klosterman—the slacker label has had a nigh indelible run. It is really time for a more thorough accounting of XersOC (Xers of Color). Yeah, anytime you attempt to label something that is diverse, it is almost impossible to craft something that both accurately encompasses the thing under review, and not be corny. I’ve failed on both these counts, but here’s the reasoning.

As stated, Black and POC GenXers (focusing just on the US as this is the origin of the discourse) have had very different generational experiences. Unless I’m mistaken and Black and POC GenXers identify with the characterization—I’m open to corrective feedback—we were in an entirely different lane. I’ll even go further. The “slacker” narrative hit first and had more money and social propulsion behind it that it became the dominant narrative. While I wasn’t fully immersed in white people and white culture, I’ve been the chip on the cookie plenty of times (undergrad, anyone?) and I didn’t know any slackers. And this is taking into account living in Minneapolis, Brooklyn, and London during my formative years. Folks seem to forget that hip-hop is a cultural artificial of GenX. While many of the originators are Boomers, it was GenX that turned hip-hop into the global cultural and financial powerhouse it is today. As my younger relatives would say: #ItBeFactsTho

There wasn’t a GenXer I knew that was lazy. Ever one of them hustled. They were abundantly creative, motivated, and open to cross-pollinating with others. I’d argue that a characteristic of my growing up, my GenX experience, was the refusal of cultural silos. Of course, there was some pretty intense racial segregation, but if you were a non-racist creative, you rocked with whomever enhanced the creative vibe. Once again, I can only speak to and for my experience, but this was how we got down.

Hip-hoppers, who inherited the culture from people who dressed like gender-fluid punk pirates who embraced the misuse of technology, didn’t really care too much for labels. This came later, with the rise of hip-hop journalism and the need to categorize the culture, and its exponents, to make it legible for those not part of the hip hop nation. We were the original remix culture. We didn’t just rehash, we reshaped. Reused. Reinterpreted. An entire folk culture sprang up from the ashes of Black and Brown poverty and reshaped the entire world. That’s super heavy when you think about it. While I’m over her harping on the virtues of hip-hop, we were also fed by the punk and hardcore scenes. Bad Brains. Black Flag. Minor Threat. JFA. These bands were just as important to some hip-hoppers as Run DMC. Hell, rebel skateboard culture is a whole other essay. An old graduate school professor of mine called GenX, “the smorgasbord generation. You bastards took and used it all, but it was never about appropriation. It was always about trying to find a clearer vision and paths for yourselves.” This is a verbatim quote. It struck me because of the transcultural nature of our friendships.

My crew alone had Puerto Ricans (one half of me), Jamaicans (the other half), African Americans, Vietnamese, a lone Czech, a couple of Irish folks, and the Hmong homeys. We were family and you couldn’t tell us anything different. And just like a family, we all had our own styles and ways of being, albeit unified by the language and expression of hip hop. No one tried to act like the other—no one slipped in a random “nigga/nigger” to try and be too down. And unlike many families I’m familiar with, our politics were relatively aligned. Naive, yes, but aligned.

We wanted to change the world for the better.

That’s it. Our desire was just that broad and unspecific. But the impulse to change the world was genuine, if a little earnest.

But how? We were all project/poor kids with zero resources. What could we possibly do? What was being done? Hip hop showed us hood kids could rise up and out of their circumstances and affect the world. Maybe we should start rapping? Get a record deal (yeah, those mattered back in the day), go on a world tour, and then people would listen to what we had to say like we listened to Public Enemy and KRS. It’s kind of hard to start a rap group when not a one of us could rap, so we explored other options.

One day, some of us were in a record store, I think it was a Tower Records, and right next to the magazines, there was this row of multi-colored books ranging in size from pamphlet to over-stuffed Reader’s Digest. Crude pictures, crap photographs, and misspellings made up the form of the thing. But the content? Whew! The content was revolutionary.

Interspersed with information about all kinds of punk and hardcore bands (and a few covering science fiction) was information about vegetarianism, and feminism, queer power, and the straight edge (sXe) lifestyle. If Public Enemy and The Autobiography of Malcolm X awakened my Black political awareness in ways other things did not, these ‘zines awakened me to the possibility of not being so narrow-band with what I cared about. The expanded my politics.

What also impacted us was that there were addresses on the ‘zines we could write to. Whether it was to contribute or to get something in return, that we had a direct line to people who were making themselves known, who were getting their ideas out into the world, touching people like me and my crew…it was heady. It felt as if anything were possible.

We pooled our money, bought a handful, and went back to Kuam’s apartment to plot and plan.

With research in firm hand, we were going to start a ‘zine.

What would our ‘zine be about? We cared about a whole lot. It had to be hip hop-influenced, that was a given, but it also had to speak to larger issues. Before word one of content was crafted, we batted around names. I wish I could remember all of them, but here are a few choice ones: “Boombox,” “Records and Pens,” Afrikan Dispatch.” What we went with was, “Mind Feast.”

It was so bad. I know.

It took us about two weeks to create a first issue. Distribution wasn’t even on our minds. That we said we were going to do something and did it, that was almost enough for us. We had issue one of “Mind Feast” but didn’t have a single clue what were we going to do with it. Earning money from it would’ve been nice, even though that wasn’t our goal. But there was no way we were going to make money from one issue. We talked about sneaking into the library or teacher’s lounge at school and using the mimeograph machine to make more. But most of us were an incident or two away from expulsion, so we decided against it. Gordon (R.I.P.) said his half-brother worked at a place called Kinko’s that had machines that could make copies for us “super-fast.”

Other, more well-funded schools, had copiers. Not ours. We cranked and inhaled toxic ink on the regular.

When we decided to go to the half-brother’s Kinko’s it was like prepping for a religious pilgrimage. We checked and rechecked “Mind Feast” to make sure the pagination was correct. We made sure the scotch tape holding our poorly shot photos in place didn’t have any bubbles. We shared what we hoped would happen when “Mind Feast” finally hit the world—we were absolutely sure that our words, our photos, our crude drawings would fundamentally alter our collective reality. We were going to make a difference. Everyone would be touched by our nigh-holy fire. We were going to change the world. Distribution never entered our minds.

As we approached the establishment, the blue, lowercase letters with the red dot over the “i” was more impressive than it should have been. But to a group of project kids, anything not covered in piss and badly scrawled graffiti might as well have been a living Nagel drawing.

We all hesitated before I strained to open the heavy glass door, struggled while holding it for my crew to step across and through. Immediate 7-11 vibes, but without the multiple colors offered by snack and candy packaging. It was less mountaintop, and more like the waiting room of enlightenment. But still full of expectation and potential.

Machines everywhere. Machines we had zero context for. Rows of Apple IIc Pluses, their putty-colored exteriors brimming with possibility. Reggie, the half-brother in question, summoned us with the universal head nod and we obeyed, basically drifting over to him. He and Gordon dapped each other. I gave Gordon “Mind Feast” and Gordon ceremoniously handed it over. Reggie went through it a few times and I saw a change in his face. I couldn’t figure out what he was feeling, until he eventually said, “Yo, this is dope, B. For real.” He then got to work making copies. Not only did Reggie make us copies for free, he introduced us to the concept of the saddle stitch. In about any hour we had a box full of the first issue of “Mind Feast.”

Before we left, Reggie was adamant that this was a one-time thing—making our copies for free—but he said he could give us a ‘bulk discount’ and then told us about a software program called Pagemaker. A program that could make laying out our ‘zine, “easy as a muhfucker.”

Holy shit.

“Mind Feast” only lasted one issue. Gordon’s death irrevocably fractured the crew. In our communities (aside from the Irish homies) we were never taught or allowed to grieve in a healthy way, so we exited each other’s lives, figuring that not being reminded of his death was the best way to confront our traumatic loss. But that one issue? We showed it to Mr. Grier, our English instructor and he told us to not give it away for free, which was our plan, but to sell it. He encouraged us not to guide our gifts away for free, otherwise people will take advantage of you and never pay you what you’re worth. A lesson I continue to hold dear. That one issue sold for $2 a pop and made us superstar intellectuals in our school. Our peers couldn’t believe that these badass, always in trouble, frequent principal office visitors could do something like that. We had 60 copies and sold them all in a couple of days. We made $120 bucks and split it evenly. We never intended to make money, but it felt good to make money legally and not via the pettiest of thefts. This brief success set me on my current path of trying to live the life of a creative. I’ve been successful, more or less. Had some great highs, and some painful rejections. I’ve even had a very well-known global arts figure steal and profit from my work. Twice. Same guy. But whatever gets to the public’s consciousness first becomes fact. So, trying to reclaim my ideas looks like theft to those who don’t know. But all in all, I’ve been able to curate a creative existence.

But when I get down about my lack of success, or when my past traumas decide to take residence in my present, I give myself permission to access those feelings that Kinko’s instilled in me. That my words, pictures, and photos could be replicated and put in a form to be disseminated to others, in hopes of finding and linking with the like-minded. In hopes of changing the world.

When FedEx office bought out and took over Kinko’s, I had a very visceral anger. Their blue and orange created by corporate committee logo was more foreboding than the welcoming and unassuming OG Kinko’s. Fed Ex was short for Federal Express. No life. No story. Kinko’s, as the story goes, was named after the founder’s curly hair. Heart. Warmth. Human. Can’t go wrong with that.

If there was an ultimate legacy bestowed by our times engaging with kinko’s is that things are possible. That you can dream, plan, and then execute. Ideas didn’t have to live in your head. They could be produced and replicated, stapled and disseminated.

And it did not hurt to have the hook up.

Notes on Experience

So we’re back at the central thesis: What makes for an effective experience? An experience that a participant will remember, cherish, and want others to have what they’ve received?

Read More